The last few years the definition of “immersive journalism” has been popular and widely used in journalism studies and journalism circles. According to Nonny de la Peña “immersive journalism is the production of news in a form which people can gain first-person experiences of the events or situation described in news stories” (de la Peña et al. 2010 at Pérez-Montoro, 2018:69-73).

Immersive journalism can bring the viewer to different emotional and physical human geographies placing in the center an event having the sensation of really being there. This sensation allows the user to better understand a certain reality and to obtain a more complete image. In those simulated digital environments, the user is isolated from the environment and has the ability to look around and to interact with the content. Interactivity is linked to the gaze: that is, the agency of the viewer is that of looking in any direction or to make choices or select different paths. Immersive journalism evolved along with an increasing focus of journalism on emotions to connect with the audience and the growing understanding of the importance of the audience to journalism. In 2015, when The New York Times launched their VR-app in collaboration with Google (distributing one million Google Cardboard headsets to the newspaper’s subscribers), in many ways marks the year when immersive journalism was introduced to larger audiences. The app allowed readers to experience a documentary about the global refugee crisis through three independent stories. The success of the project naturally exceeded all expectations; however, it was the level of emotional involvement and engagement of the readers that came to mark VR in immersive journalism as an “empathy machine” (Bruni, Kadastik, Pedersen and Dini, 2022:51-52).

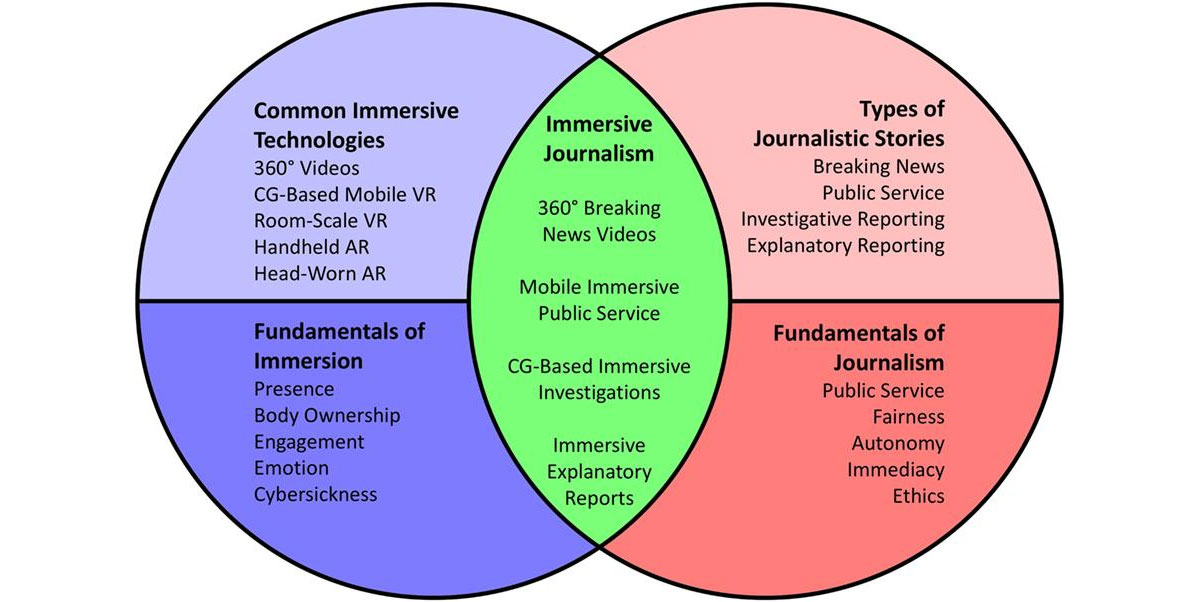

Source: Hardee, G. M., & McMahan, R. P. (2017). FIJI: a framework for the immersion-journalism intersection. Frontiers in ICT, 4, 21.

Immersive journalism contributes in the creation of a stronger connection to a news story by enhancing the audience’s presence in the virtual representation of the real-world event. For immersive journalism to move higher on a presence continuum and optimize VR as a journalistic communications channel, then enhancing embodied engagement with the Virtual Environment and the narrative is key. Immersive journalism reaches a higher level of immersion if the devices used for watching the news succeeds in isolating the user from their physical reality. Immersive journalism needs yet to improve clear guidelines and principles aimed at journalistic immersion and not just at technological immersion, i.e., to renew its narrative strategies by having as a reference its core social functions and the associated ethical frameworks (Pérez-Seijo, Vicente, & López-García, 2022:12-14). Immersive journalism enables witnessing emotions and confirms the close relation between VR and emotion in general.

Experiments with immersive journalism have posed two main challenges to traditional journalism. The first challenge has to do with how we should think about image-making and its study in journalism. The second challenge is about how we should discuss the role of the body of audiences within the production and consumption of journalism. For immersive journalism to be ethical, the tools of fabrication should be visible to the viewer. Emphasis on the body and on the ability to act is the fundamental difference between immersive journalism and other forms of journalism that heavily rely on vision and sound, such as photojournalism and broadcast journalism. 3D-based immersive journalism that requires full bodily participation brings to the fore the limitations of theoretical approaches from visual journalism, as it introduces the problem of the place of the body in journalism production and consumption. Conquering the bodily experience of audiences seems to be the primary goal of immersive journalism.

Immersive journalism has expanded the boundaries of storytelling creating new relations with the audience, fostering, at the same time, a series of innovations that impact the entire profession, from the moment that news is reported, to the process of distribution, and audience reach at the receiving end. Immersive journalism can lead to greater compassion having one or more protagonists telling the story—which will produce more understanding, stronger empathy and a feeling of getting into someone else’s situation. In ethical guidelines for immersive journalism, the audience dimension should be considered as partners in the construction. Generation Z, according to Herrera Damas and Benítez de Gracia, (2022:338-342), is the one in which newsrooms are going to target in immersive journalism.

Bibliography:

Bruni, L. E., Kadastik, N., Pedersen, T. A., & Dini, H. (2022). Digital Narratives in Extended Buchholz, F., Oppermann, L., & Prinz, W. (2022). There’s more than one metaverse. i-com, 21(3), 313-324. https://doi.org/10.1515/icom-2022-0034

Herrera Damas, S., & Benítez de Gracia, M. J. (2022). Immersive journalism: Advantages, disadvantages and challenges from the perspective of experts. Journalism and Media, 3(2), 330-347.

Pérez-Montoro, M. (Ed.). (2018). Interaction in Digital News Media: From Principles to Practice. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-96252-8 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96253-5

Pérez-Seijo, S., & López-García, X. (2019). Five ethical challenges of immersive journalism: a proposal of good practices’ indicators. In Information Technology and Systems: Proceedings of ICITS 2019 (pp. 954-964). Springer International Publishing.

*Ioanna Georgia Eskiadi is a Ph.D. Candidate on new emerging technologies and journalism in the Department of Journalism and Media Communications, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki. Researcher in the Peace Journalism Laboratory, AUTH, and member of Digital Communication Network. She holds a Master of Arts in Crisis Journalism and Risk Communication and a Bachelor of Arts in Journalism and Mass Media Communication from the Department of Journalism and Media Communications, AUTH. She has received various scholarships and fellowships and she has collaborated with international organizations as a researcher (Portulans Insitute, NATO, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung Greece, and Cyprus). She speaks English, German, Italian, Spanish, and Arabic.